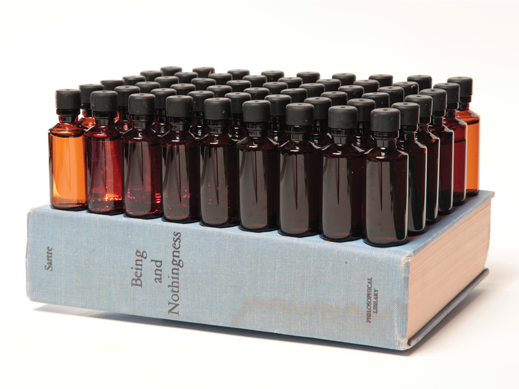

Being & Otherness, 2014

Darien Taylor in conversation with artist Andrew Zealley.

Andrew Zealley is a queer shaman. He believes that art can heal. Through his art, and in the way he lives his life (his art and life can hardly be separated), he is constantly on the lookout for the ingredients of a magical healing compound that will soothe queer minds and bodies.

I first encountered Andrew in the late 1970s, when he was part of Toronto’s Queen Street West scene, playing in the queer proto-electro band TBA at the Beverly Hotel, the watering hole of art students and other disaffected youth at the time. I bumped into him again years later when he played with the band Greek Buck. As an audience member I thought, simplistically, that Andrew was a musician. But over time I learned that he is so much more.

First of all, Andrew is not as interested in music as he is in sound itself: energy-filled, often jarring and awkward sounds—and silences—that do not come together in a way we traditionally think of as music. His sound work requires our ears to listen and our minds to hear in new ways.

Secondly, Andrew’s art has evolved beyond his sound-based work to include ritualized performances, as well as conceptual art, which he often documents in photos, videos and art books. In these works, he continually explores themes of sex, love and healing.

From the 1980s onward, Andrew’s art has documented his relationship to HIV—first as a caregiver, then as a person living with HIV, and always, as a healer. He and his works present an integrated, compassionate and optimistic view of HIV as a journey to health.

Darien Taylor: When did you first become interested in art?

Andrew Zealley: My interest in music and sound reaches back to childhood. I could often be found in my bedroom closet, as a child, with my older sister’s portable record player, moving the records backwards and forwards with my fingertip, exploring the strange sounds these gestures produced. So, I was always into sound and music.

My father was a professional artist with a studio in our home, and my parents always encouraged my interest in art. In 1970, when I was 13, my father bought me Yoko Ono’s first LP with the Plastic Ono Band. Six months later, my mother bought me my first set of headphones for my birthday!

I remember buying a copy of FILE Megazine as a teenager, which had a big influence on me. FILE, published by the artist collective General Idea, documented the queer, subversive underground art scene that was shaking up Toronto and other international urban centres at the time. It completely altered my understanding of art, merging glam rock and punk sensibilities with references to Art Deco and 1940s nostalgia.

DT: What sort of impact did HIV/AIDS have on the arts scene?

AZ: It became a galvanizing force for the city’s arts community. In the 1980s, crosstalk between the visual arts, music and performance worlds was exploding. When AIDS hit, the interdisciplinary arts scene was already vibrant. It was a wonderful time artistically speaking, and a fucking scary time in terms of sex and queer identity. Many queer artists in the city rallied around the AIDS flag as a survival strategy. We held on to each other. The arts community, the queer community and the HIV/AIDS community were bound together in that moment.

DT: Much of your work explores the medium of sound. Can you tell us a bit about the sound work you’ve done?

AZ: Throughout the 1980s, I wrote music and played in successful pop bands like TBA and Perfect World. In the 1990s, I began to score for filmmaker John Greyson, and in 2000, I co-produced the theme song to the hit TV series Queer as Folk.

Listening is part of the environmental writing course I currently teach at York University. To me, listening is not limited to listening with the ear alone, it is also about “deep listening,” which involves feeling the vibration and movement of sound.

DT: You collaborated with visual artist Robert Flack. Can you describe that work and your relationship with Robert?

AZ: In 1989, I started collaborating with Robert Flack, who tested HIV positive around the same time as I was confronting serious liver issues.

We researched alternative healing methods, visual and audio representations of body, mind and spirit, and histories of queer people as shamans and healers. This collaboration resulted in the exhibition Empowerment, at the Garnet Press Gallery, in 1991—a series of prints that depict the chakra points on the body accompanied by an ambient soundtrack. The images and sound installation from this show are now in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

I was the last person to be with Robert before he died in 1993. He was in the old Wellesley Hospital.

An artist friend, David Rasmus, had arranged some of his beautiful photographs of flowers and sky on the wall, facing Robert. Robert was very quiet that evening. His copy of The Tibetan Book of the Dead was on the bed at his side. I turned my chair to sit abreast with him. We sat for hours in silence, gazing at Rasmus’s blossoms, blue skies and white fluffy clouds.

When I left, he quietly said, “Just keep working on your music.” I have never faltered on that instruction.

DT: And then you yourself became HIV-positive….

AZ: Yes, I seroconverted in 2001. At that point, my art had already focused on AIDS-related issues for over a decade. So I thought I knew the issues, but I hadn’t anticipated the challenges of HIV “on my own skin,” so to speak.

Andrew Zealley in front of “shadow prints,” photographed by Roberto Bonifacio, 2015

DT: Did the meaning of self-care change for you after you became HIV positive?

AZ: When I tested positive, I doubled down on my self-care. I got serious about what I put into my body—clean water and good food, lovingly prepared. At first I had problems with the side effects from my HIV treatment and it wasn’t until 2009 that I found a treatment combination that worked for me.

My AIDS-focused art and self-care have evolved side-by-side, and this connection deepened after I tested HIV positive.

DT: Art-making offers a kind of healing for you. Can you talk about some of the work you have done post-diagnosis and its relationship to healing?

AZ: Music can offer rich healing experiences. Look at disco music and the community-building that erupted in its wake!

In 2004, I worked on two significant sound pieces with AIDS themes. One is “Five Nocturnes for Electricity,” published as a vinyl-only edition of 100 with an edition of photographs by General Idea co-founder AA Bronson. The sound pieces explore dreaming and healing. They reflect on Bronson’s photos of gay men naked in their beds. Together, the sound and photos offer ways to reimagine the bed as a place of nurturing and love instead of a place of death, as it was in the pre-HAART era.

The second piece was a performance organized by Ultra-red, an artists’ collective working in sound and political activism. It took place at the Art Gallery of Ontario, as part of the 2006 International AIDS Conference. The artists recorded statements from conference delegates. As the layered sound was broadcast into the large space at the art gallery, the result was a massive, deeply energizing roar of sonic emotion. Remixes by the artists are available online for free download on Ultra-red’s site.

The processes involved in researching and producing artworks can be healing, and sometimes the works convey ideas of healing in and of themselves—for example, Being & Otherness, a piece that is from a larger body of work titled Black Light District.

I started with a copy of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, a seminal existential text that had a big influence on me when I was around 17. The photograph features a first edition hardcover copy gifted to me by a former teacher-friend, and a series of glass bottles with rubber stoppers. The bottles unambiguously suggest amyl nitrate, an inhalant used to enhance sexual practices that is now banned in Canada. The piece speaks to the othering effects of both the drug and the book as ways to achieve what I would call the “privileged position of outsider.”

DT: You returned to school around this time…

AZ: Yes, to the Ontario College of Art and Design University in 2011, after 32 years away. This decision was prompted partly by my HIV-positive status, as well as a desire to challenge myself and a goal to teach. It was a powerful moment for me, to draw together my creativity, my health concerns and my interests in queer people as healers and shamans.

DT: How has your current work at York University continued to examine themes of healing and self-care?

AZ: My PhD research involves a studio residency project at the Toronto People with AIDS Foundation, called “This Is Not Art Therapy.” My aim is to show that making and responding to art can offer healing that is different from the pathologizing tendencies of the art therapy model commonly offered to people with HIV. The project is guided by a simple inquiry: What becomes possible when artists are visible and active in AIDS service organizations?

I think it’s time to bring artists into community-based AIDS organizations in roles similar to complementary care practitioners.

DT: How does this challenging work affect your own health?

AZ: The challenges and rigour of graduate studies appear to be beneficial to my health. My HIV-related numbers have never been better. By focusing on my studies—which are related to HIV status, health and community, and are entangled with arts—I see and feel my body responding in positive ways.

Check out more of Andrew Zealley’s work at www.andrewzealley.com.

Darien Taylor is CATIE’s former Director of Program Delivery. She co-founded Voices of Positive Women, to empower and support women living with HIV, and is a recipient of the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal. Darien has been living with HIV for more than 20 years.