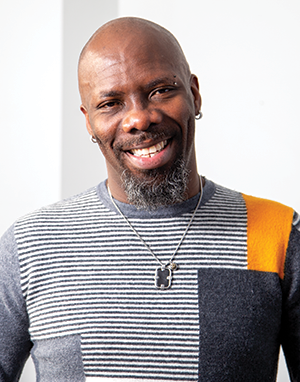

Fueled by his commitment to social justice, Gareth Henry stands up for the rights of LGBTQ people around the world.

By Sarah Liss

For Gareth Henry, altruism is less a choice than a vocation—he’s perpetually, inevitably drawn to opportunities to help others. Gareth arrived in Toronto as a refugee in 2008, fleeing persecution and certain death as a prominent out gay man in his home country of Jamaica. Since then, he has committed himself to improving the lives of others. The 41-year-old activist and advocate has worked to connect members of marginalized groups with vital resources (at The 519, a community centre that advocates for LGBTQ people, and at Kids Help Phone) and he’s currently the director of programs and services at the Toronto People With AIDS Foundation (PWA). In 2009, he joined Rainbow Railroad—first as a volunteer and now as senior program officer—to help bring LGBTQ folks fleeing violence and persecution in their home countries to safety. Since then, he has worked with and supported more than 350 individuals from the Caribbean seek asylum in Canada, the U.S. and Europe.

While growing up in St. Mary, in northern Jamaica, Gareth started to feel compelled to care for others around the same time he was becoming aware that he was gay. That was in 1985, at the age of eight. “I’ll always remember that summer,” he recalls. “I was trying to locate myself, to find the space where I could be accepted.”

For a queer kid being raised in an intensely homophobic culture, that process of self-discovery was inflected with anxiety and confusion. Gareth describes watching a football coach in his community who was rumoured to be gay dodge items that were thrown at him as he walked to his office. “He was known as a batty man [Jamaican slang used to refer to a gay man]. My mom and stepdad would say, ‘Don’t become like him!’ People would warn, ‘Cross the street when you see him! Don’t go close to him! Don’t let him touch you!’ I knew that wasn’t right,” Gareth says, “but I also didn’t want that to happen to me.”

For some, that roiling mix of homophobia and fear that Gareth experienced might spark an impulse to persecute other outsiders, but for Gareth, it fed his sense of social justice and responsibility. Even as his growing awareness of his own sexuality led him to turn inward, empathy prompted him to reach out. He noticed that this football coach who was painted as a pariah seemed to be a good person. “So I started to talk to him,” he says. “We never had much conversation, but I needed that to help normalize the experience for myself.”

Connection and belonging would not only become driving forces in Gareth’s personal life, they would eventually provide the through line for his life’s work. As he was contending privately with his own sense of otherness, the young boy found solace and a sense of community in a somewhat implausible space: the church.

Religion was sacrosanct in his household. His mother and grandmother tried to “protect” him by sending him to church on Sundays and Saturdays. (“That’s a lot of Jesus!” he quips.) Though sermons about Sodom and Gomorrah might not seem particularly encouraging for a young queer kid, Gareth grew to love church because, he says, “it was a place I felt safe. Outside, people would call me names; in church, I didn’t hear that. I knew what to do: I would sing in the choir, I could quote scriptures!”

To be sure, the fire and brimstone gave him pause: “On the one side, it felt good to talk about Jesus and love, but then you’d hear the hate coming from the pulpit. How could these be the same people?” Even so, Gareth was tempted to get involved in ministry. For him, the essence of church was a commitment to loving and supporting people. “I loved taking missionary walks—going out in the street to find people in need. I loved helping people in the hospital. I loved seeing people happy. I was the little boy who’d leave school to lend a hand. Neighbours would call me to wash their dishes. My mom had such a hard time with me—she’d say, ‘You need to say no!’ But I couldn’t. I always just wanted to help.”

Gareth’s vague notions of becoming a minister persisted into his teens. After graduating from high school, he moved to the capital, Kingston, and enrolled in college. At 19, he made a connection that would change his life. While working in customer service for Jamaica’s revenue department, he began chatting with a customer by the name of Gladstone Allen, with whom he quickly became friends. The two conversed in the coded, nuanced, subliminally loaded way common to kindred spirits who, for reasons of survival, keep their sexuality covert. Eventually, Gladstone invited Gareth to join him in the evenings to attend meetings with others who, like them, were outlaws of a certain kind.

The purpose of the organization that ran the meetings, Jamaica AIDS Support for Life (JASL), was to spread awareness and support people living with HIV. But practically speaking, as a safe haven in an inherently homophobic culture, it was also an oasis. “I walked into the space and saw men galore!” Gareth recalls. “I saw guys in dresses, butches.... I’d never seen so many people who were deemed to be different in one space.”

Though he insists he’s shy in most of his life, Gareth was utterly transformed by his exposure to the group. As he tells it, he had seen men “beaten, chopped and chased through the streets by angry mobs.” He’d witnessed people around him suffering and wasting away from AIDS in silence, too terrified of HIV stigma to open up about their diagnoses. He’d heard about lesbians being subjected to corrective rapes, about friends who had lost their jobs and been abandoned by their families simply because of their sexuality or because of rumours that they were HIV-positive. Though he knew that attending these meetings might put him at risk—he’d be more easily identified as gay, more easily “tainted” by negative gossip—Gareth was so moved by the work JASL was doing that he immediately signed on.

JASL’s motto was simple: love, action and support. Every Tuesday, they would join together to sing what became their de facto theme song: Dionne Warwick’s “That’s What Friends Are For.” “It would always bring the room to tears. It would motivate and inspire us that amidst such hate and violence and the uncertainty of whether or not we’d live to see the next day, we had each other, in that moment, in that space and time.” Here is where he found his voice. He felt empowered to challenge the negativity that surrounded him and his peers. “I wanted to fight back and stand tall with my community.”

Gareth signed up as a volunteer to visit people dying of AIDS in hospice. Before long, that volunteer position morphed into paid work. “I didn’t know much about HIV,” he recalls. “I didn’t know anything” beyond rumours. But he quickly learned, thanks to his passion for the work and the careful mentorship of the man who hired him. “We were the only place of refuge for people with HIV,” he says. “I’d see 40, 50 people walking into the office in very bad shape on a daily basis. It broke my heart, but I realized we were a beacon of hope for folks—they could come to us and talk and feel loved.”

By the late 1990s, the homophobia simmering in Jamaica had reached a boil: Anti-gay rhetoric was embedded in the lyrics of songs and in the political speeches of people running for office. Inciting violence toward sexual minorities was viewed as a viable way to appeal to the masses. Fuelled by a desire to push back against this onslaught of hatred, a group of men and women, most of whom were affiliated with JASL, came together and started an advocacy organization in 1998, which was housed at JASL. It was called the Jamaica Forum for Lesbians, All-Sexuals and Gays (J-FLAG)—and Gareth was eager to be a part of it.

“I was a kid and had no idea what was involved in building an organization,” he says. “But I figured that if I was engaged and designed my own role, I could be part of it.” He started out fetching coffee and water. “I became more and more involved and more and more excited. I realized, ‘this is where I fit in.” In 2004, Brian Williamson, J-FLAG’s spokesperson, was murdered. Gareth stepped up to take over as the face and voice of the organization.

It’s not that he was unaware that being a visible gay man in Jamaica put his life at risk. Within five years, 13 of his friends were killed as a result of hate-motivated attacks. But he was compelled to move forward, to believe, with almost religious fervour, that he could make a difference for himself and his peers. With J-FLAG, Gareth says, he found a sense of fulfillment akin to what he experienced at church. At university, he turned his attention to social work, to ensure that his professional path would dovetail with his personal passion.

But by 2007, his efforts to better the lives of LGBTQ people had made him a target. He was beaten repeatedly, once by four police officers, in front of over 300 bystanders. Gareth went into hiding but couldn’t escape the death threats, the violence and the fear that his next encounter with an unfriendly face would spell his demise. When he accepted that it was time to leave, his public profile was a boon: It was clear that Gareth’s actions as an out gay man had put his life in jeopardy, and he was granted asylum in Canada as a refugee.

Gareth’s mother followed four months later. And his sister and nieces arrived in 2012, after media reports about a petition he had launched against the Jamaican government resulted in people harassing his family members. “Neighbours put homophobic signs on their gates, the kids were bullied. I felt horrible. Because I chose to be my authentic self, those who love and care for me became victims of homophobia. Their lives were forever changed simply because they chose to love, rather than hate.”

To say Gareth views his work as a matter of life or death is no exaggeration. He is acutely aware of the stigma that can be associated with an HIV diagnosis. Two decades ago, when he first joined JASL, the situation at home was dire: “People were dying alone, at home. Sometimes people were afraid to leave our office because they were afraid they’d be seen. They’d worry about getting sick, about visiting a clinic.” Many young people were wary of accessing vital services because they feared being spotted; the consequences could be deadly. “I had partners who died from AIDS because they were too ashamed to get care and support,” Gareth says. He describes how he became a primary caregiver for Gladstone Allen, the dear friend who had initially introduced him to JASL. “We wound up living together, and he became unwell. He lost his job because he couldn’t work. He didn’t want to go out, he didn’t want to go to the hospital.”

“As he was dying,” Gareth says, “he said, ‘Whatever you do, don’t get this, don’t get AIDS. Promise me you won’t let this happen to you.’” Gareth couldn’t make that promise. He had been assiduous about getting tested, but in April of 2003, Gareth had learned that he was HIV-positive. He had no remorse about his status, but he felt compelled to protect his friend. “I let him die peacefully and with the thought that I wouldn’t have to go through the stigma, discrimination and hatred he went through.”

From that moment on, he says, “I vowed I would never be ashamed to tell anyone who asks—I’m positive. My status did not change my life. It altered my perspective on the people around me.”

Certainly, being positive in Toronto in 2019 is leaps and bounds ahead of contemplating life with HIV in Jamaica in the late ’90s—or even the early 2000s. Yet Gareth is cognizant of the subtle and not-so-subtle hierarchies that exist for those in need of support and resources. It’s one thing to be a privileged, white, cisgender Canadian citizen with health coverage and family support; it’s another to be a newcomer who doesn’t speak English, a street-involved youth, an individual contending with precarious housing and employment. “My job is to make sure people have access to what they need to live positively being positive,” Gareth says. “It’s very difficult to keep your head above water. Sometimes the HIV stigma is so subtle, and in this day and age, it’s horrific when I listen to a client talk about the difficulty they have accessing services in the city or about not being able to disclose that they’re positive. I want to continue to create awareness and to make sure we’re doing whatever we can to hold people accountable.”

Given the psychological and physical violence Gareth endured, the trauma of having to identify the bodies of loved ones, the psychological toll of ministering to ailing people as they face the end of their lives, it’s hard to imagine where Gareth finds the personal resources to fuel such emotionally demanding work. He claims it’s all about balance.

“I’m vigilant: I work hard at two jobs [PWA and Rainbow Railroad], and to keep up my life and relationship, every three months my partner and I pack our suitcases and go somewhere where we can do silly stuff and have cocktails on the beach.” Self-care, he explains, is paramount. Still, beyond Gareth’s regular getaways, he insists it’s the work itself that gives him strength.

“Every so often, I ask myself whether this is what I should be doing,” Gareth muses. “I think I’ve been involved in advocacy and activism since I was 20, so that’s the last half of my life. And there’s not one day where I’ve regretted it. My mother always said, ‘You know, boy, you just can’t say no.’ When I tell someone no and they walk away, it pains my heart. There’s a more nuanced way to engage with people. How can I inspire you to take ownership over your life? How can I inspire you to make change for yourself?

“I know what it is to be at the bottom of the barrel and treated as an outcast,” he adds. “No one deserves to be treated that way. If I can turn that around for one person a week, that makes me happy.”

Sarah Liss is a Toronto-based writer and editor whose work has appeared in The Walrus, The Globe and Mail, The Hairpin, Hazlitt, Toronto Life and Maclean’s. She is also the author of Army of Lovers, a community history of the late artist, activist, impresario and queer civic hero Will Munro, published by Coach House Books.

Photograph by Carlos Osorio