The 24th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2022) is taking place this summer in Montreal. It’s not the first time the city has hosted the event—in 1989 it was the host city of the 5th International AIDS Conference, which became a real turning point for HIV activism and research. We take a trip down memory lane with three activists who played a role in that historic event.

Interviews by RonniLyn Pustil

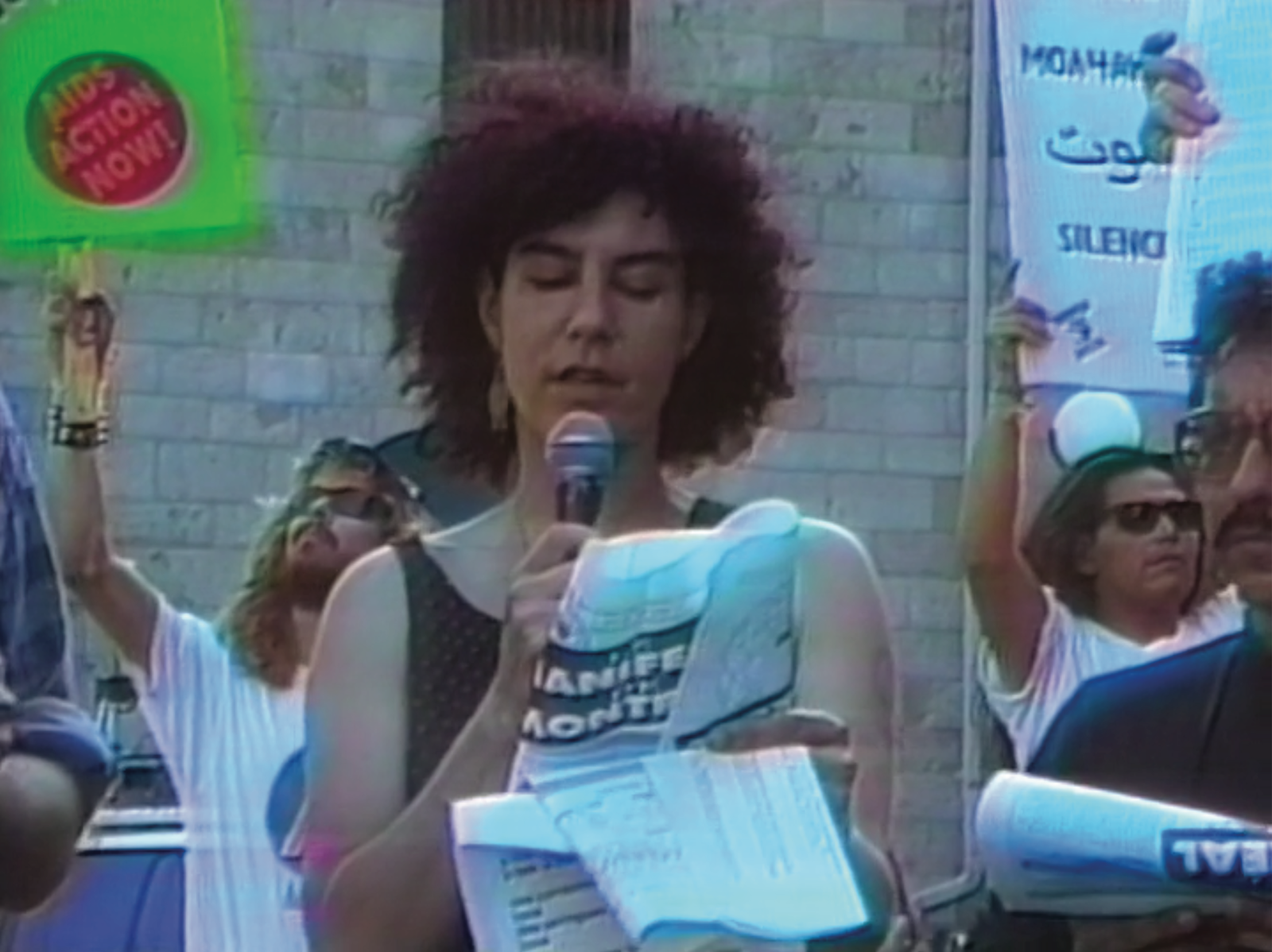

Karen Herland

Professor, Sexuality Studies and Fine Arts, Concordia University

International AIDS Conferences attended: 1

When the conference happened, I was in my mid-20s and working at CSAM (Comité sida aide Montréal) in education and prevention. It dawned on me that all these activists were coming to Montreal and there wasn’t any infrastructure to support that. Something had to happen, but one young lesbian wasn’t necessarily going to rally the masses on this one. I got in touch with my friend Eric Smith and we decided to hold a meeting. It was 1989—no Internet, no Facebook, nothing. We had phone trees and went to events and handed out fliers. About 40 to 50 people came to our first meeting in a room on top of an anarchist bookstore.

This was March, and the community was reeling from the murder of Joe Rose, a young queer boy barely out of his teens who was gay bashed to death on a bus. People at the meeting wanted to draw attention to this homophobic murder. I felt it might be a good way for us to get to know each other and start to organize together, so we developed a protest and that’s how we started. We named ourselves Réaction Sida.

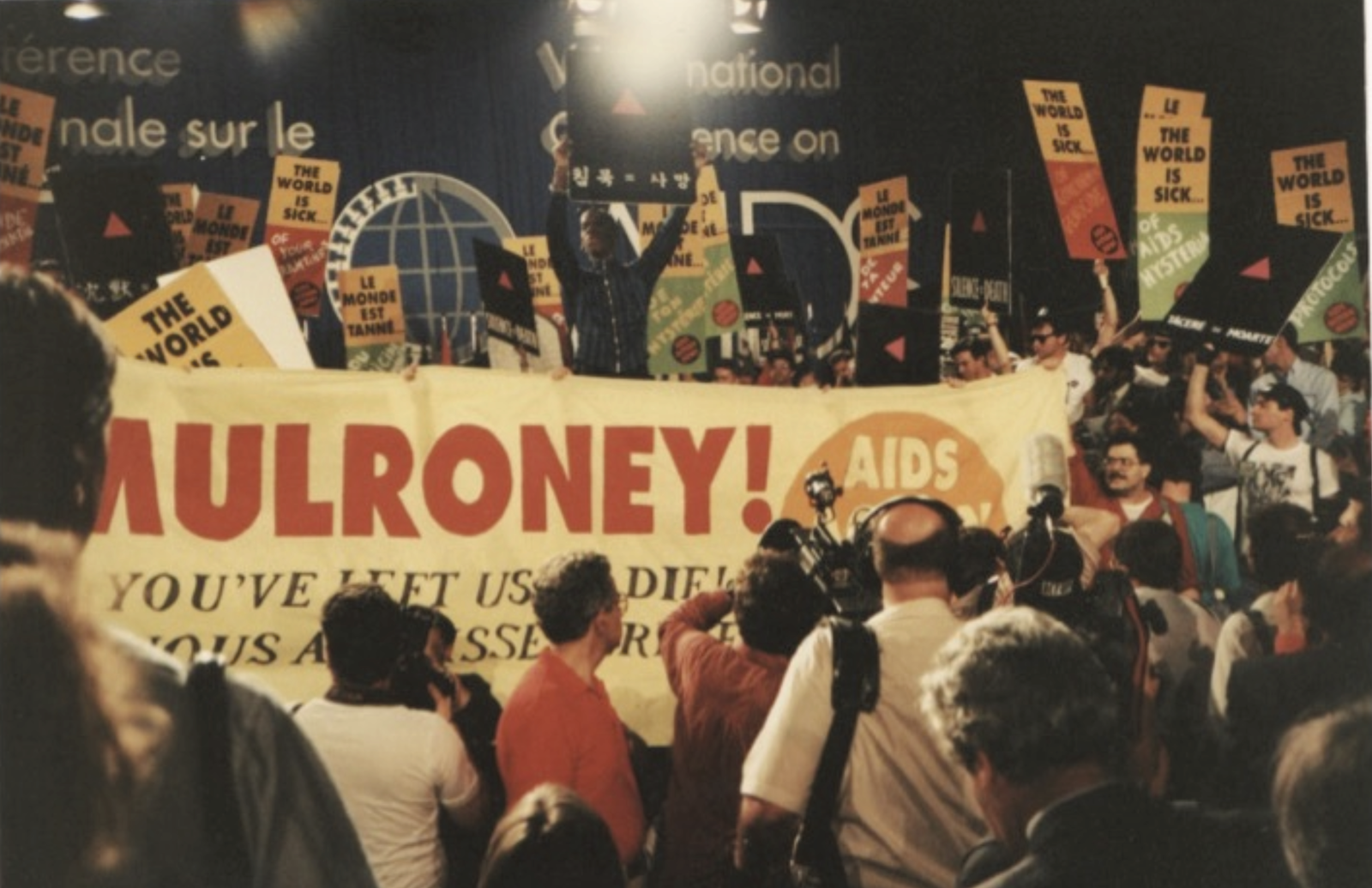

Eric found a location that we could use as our headquarters in a housing co-op and furnished it with fax machines, typewriters, rudimentary computers and a TV. It became our centre where we held meetings, wrote press releases and prepped for demos. Every night during the conference we’d watch the news together and debrief and figure out what to do the next day. We were naïve and fearless. We accessed the conference in all sorts of ways and protested and disrupted as often as we could. At the opening ceremony, we started protesting outside of the Palais des Congrès and at one point someone shouted, “we’re going in!” and everyone entered the building.

I have vivid images of us going up the escalators—this gaggle of leather jackets, T-shirts, multicoloured hair, combat boots—the whole bit. My best friend, Sally, was 5’11”, had super-tall, teased dread hair and was wearing roller skates, and she towered over everybody. We took over the stage with our banners and chanted “join us” to the audience. A lot of them stood up and cheered us on. The 1989 conference was very professional—researchers, doctors and government and public health officials were invited. The idea of people who were affected by HIV and AIDS being involved came out of that conference.

What I remember so distinctly is that at one point [AIDS Action Now! chair] Tim McCaskell said, “I want to open the conference on behalf of people living with HIV and AIDS.” Taking over the stage was important but reading what became the Montreal Manifesto in English, French and Spanish was a really important moment. We delayed the opening ceremony by maybe an hour and then left. Some of the protesters stayed to heckle [then Prime Minister] Brian Mulroney during his speech.

There were multiple actions every day on behalf of different populations and communities. Out of the hundreds of abstracts presented, only 12 concerned women—and that was entirely women as mothers or sex workers. There was no other acknowledgment of women in HIV at that time. Our actions were political but also social. I met incredible people. We spent so much time together and we were all so engaged and committed to something, but it felt like we were screaming into a void.

The events of that conference and the demands we made led to provincial assistance with a medication program that continues to this day. A lot has been written about how that conference shifted the relationship between “patients” and the scientific community. It created a situation whereby people directly affected by HIV/AIDS demanded and were recognized as having a voice in how services were provided, how programs were developed and how resources were allocated.

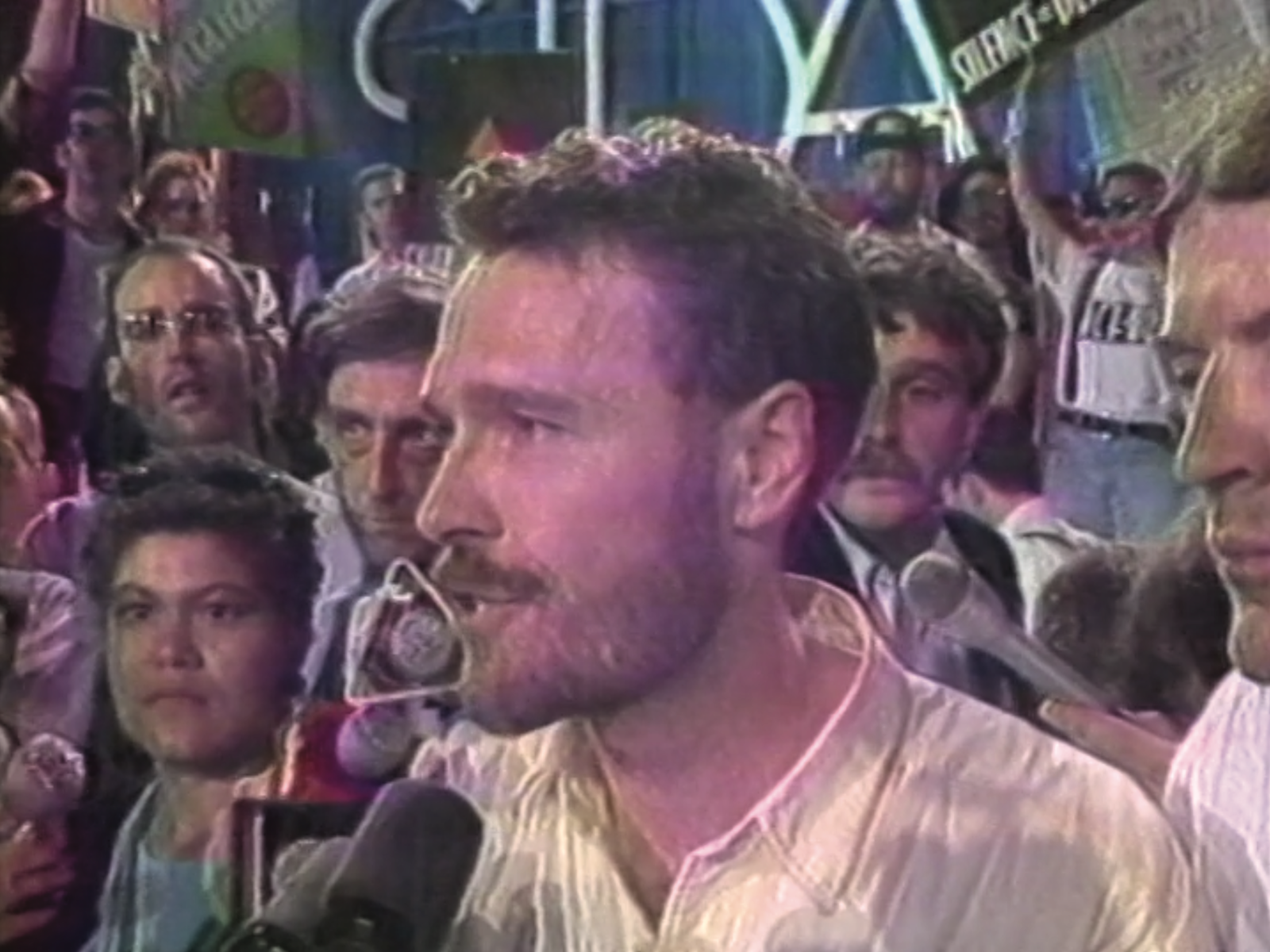

Tim McCaskell

Self-proclaimed “AIDS dinosaur”

International AIDS Conferences attended: 5

I had just become chair of AIDS Action Now! (AAN!). The conference was coming up and we contacted ACT UP New York. Up until then, AIDS conferences had been for the medical and pharmaceutical industries. If people with HIV and AIDS were around at all, we were tarted out as specimens for this, that or the other. ACT UP had sort of changed the way we thought about ourselves—not as patients but as people living with HIV and AIDS and as people who needed to change the way the epidemic had been conceptualized. People living with HIV and AIDS wanted to go to the conference to learn about the new science. We were very interested in trying to figure out whether there was anything we could do to keep ourselves alive.

I went to Montreal in March to suss out the conference site. I managed to get an actual blueprint of it, which we shared with ACT UP. We developed with ACT UP the Montreal Manifesto, outlining the rights of people with HIV and AIDS. “Nothing about us without us” was the fundamental message, and it called for more international solidarity, access to treatment, money for research and more.

In June, a gang of us from AAN! went to Montreal. A small group called Réaction Sida had found an office space just a quick bus ride from the convention centre. That was the first time there was an activist hub at an AIDS conference where we could all gather. We met with ACT UP and Réaction Sida to plan our interventions. For the conference opening, we were planning a protest in front of the main entrance of the convention centre, where different people were supposed to speak as the delegates went in. ACT UP was a bit more assertive than that. I was about to speak when I heard a ruckus behind me. The ACT UP guys had busted through the front doors and the whole ACT UP crowd started marching into the convention centre. They hadn’t told anybody else, and we were like, what’s going on?

We decided to follow them. We all marched into the conference hall and took over the stage… and then didn’t know what the fuck we were supposed to do. We milled around, waiting for Mulroney, and then somebody stuck a microphone in my face. So, as the head of the Canadian activist organization, I officially opened the conference on behalf of people living with HIV and AIDS. What I said was short and off the cuff. I basically went after the Mulroney government for its inaction, incompetence and negligence in terms of dealing with this crisis, because at that time Mulroney had never publicly said the word AIDS.

The audience clapped; they were entertained. And I think it made them begin to think of things in a different way. There seemed to be a lot of solidarity, but I also think their jaws hit the floor because nothing like this had ever happened before. These were largely medical people who were used to dealing with patients; they weren’t used to dealing with activists. After I spoke, we still had no plan. They couldn’t bring out the prime minister because there were these crazies on the stage and they couldn’t get us off the stage without a battle. On the fly, we decided to read the Montreal Manifesto. At a certain point we had to let the conference begin, so we all stepped down. A group of us sat in seats in the front that were designated for VIPs. Then security figured it was safe enough to let Mulroney speak. The conference organizers were scrambling to maintain control of the situation. I think they realized the world had shifted, because they ended up getting a person with AIDS from Vancouver to do a closing piece, which hadn’t been scheduled when the conference began.

After that year, the International AIDS Society (IAS) found a space for activists at conferences and established an activist liaison group, because they realized we were going to be there no matter what. Our action changed the character of those conferences. Everybody knew that people with AIDS were going to be active and vocal and our issues were going to be part of the agenda, even if we were not included on the official agenda, so they had to take us seriously. The IAS also began to provide subsidies for people with HIV and AIDS to attend the conferences. It meant that we were there at the table, raising all kinds of uncomfortable questions.

We managed to get compassionate access to experimental treatments. And the kind of media-savvy stunts and protests that ACT UP pioneered became part and parcel of an activist’s backpack. We really pushed to make things different.

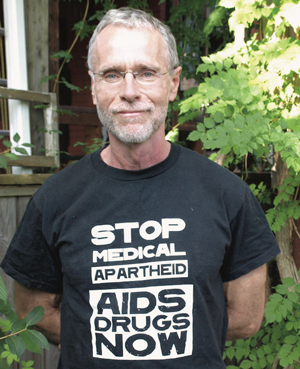

John Greyson

Video/film artist

International AIDS Conferences attended: 3

Montreal was memorable because we stormed the stage. I was a member of AIDS Action Now! (AAN!) and my then-boyfriend and I were there making a documentary about global activist voices. Up until then, the AIDS conferences had been dominated by the experts. ACT UP New York, AAN! and other grassroots and queer activists all got together and said, “We need to change the status quo. The time is now. It’s 1989 and this is the conference where it’s going to happen.” We painted banners, posters and placards. Our campaign was called “The World is Sick”—sick of multinationals, Big Pharma, President Bush. We loaded up vans for our road trip to Montreal.

The opening demonstrations were extraordinary and still the most vivid. The plan was that we would chant and protest outside of the convention centre. But were we going in? Not that I remember. Maybe some had decided. Certainly, civil disobedience was very much part of the DNA of the activism that week. There was a turning point where people started going in. We weren’t going to be politely chanting outside. We were going in. We burst through the barricades and went up the escalators. A lot of this footage is in the documentary—The World is Sick (sic)—because I was able to keep filming during the whole thing. I was one of the few people who captured what came next.

We were on the stage, Tim McCaskell seized the microphone and then, on behalf of people living with AIDS, he opened the conference. It wasn’t about asking for the microphone; it was taking the microphone. The symbolism of that cannot be underestimated. It was a critical mass of very organized, articulate global activists that went inside the building. And it set a tone for the rest of the week. That declaration, throwing down that gauntlet, gave us permission in every meeting and every context to speak out and change the agenda. After Tim officially opened, we left the stage. We had seized the stage—that was the victory, the symbolic moment—and then we cleared it. Mulroney got up to welcome the crowd. He had never said the “A” word (or the “S” word if you’re in Quebec), as Tim had pointed out in his opening remarks, so we all stood and chanted “it’s time!”

Mulroney acted like he was at a wedding party toasting the bride. The utter hubris underlined everything that had been wrong for his entire stretch. When someone is speaking absolute lies, the only appropriate response is to yell back and disrupt business as usual. The doctors and Big Pharma people who liked their AIDS conference junkets with their fancy four-star hotels and expense accounts were sort of disgruntled. But, by the end of the conference, they were claiming to be on side with the activists. It was a turning point. Doctors and government officials suddenly cared about our issues.

It was a defining moment in terms of activists on a global stage. There had been lots of AIDS activism since 1987, but this was the first time it had played out at a global level. It was a chance for us to open the door on global activism. After the opening ceremony, I mostly worked on my film, running around interviewing some of the most amazing activists from Australia, Africa, South America. Plugging into the energy and brilliance of the international activists, particularly the work of the South Africans, opened my eyes to seeing AIDS from a global perspective. I was also one of the coordinators of the cultural program; Ken Morrison was the mastermind behind it. Every night we had films, poetry readings, an art exhibit. My time at the conference tended to be dominated by those events.

One of the most important things to remember about 1989 was Tiananmen Square. The convention centre was in Chinatown, and each day we went to the arches there, where local Chinese activists were wheat-pasting updates in Mandarin about what was happening in Tiananmen. So much of our courage in breaking through the barricade had to do with the courage and outrage of Tiananmen, that feeling that there’s something in the water and we’re all catching it. There’s a new virus in town and it’s called courage!

AAN! had already lost so many members. Seeing that our government matched Reagan’s indifference and Mulroney’s contempt for people with AIDS was visceral. The medical establishment was happy to take on research projects and placidly proceed with business as usual, but there was no sense of urgency. You’re smugly having cocktails in your hotel and leveraging this for what you can expense, but a conference is not a holiday. This conference should have been about recognizing the urgency. And that’s what we brought to the stage.